On Kirtan, what makes music sacred, and his inspiration from Neem Karoli Baba

On Kirtan, what makes music sacred, and his inspiration from Neem Karoli Baba

An Exclusive Interview by Llew Smith and Annie Stopford.

The melodious, open-hearted singing of Krishna Das—or KD, as friends and fans most often call him—has carried the devotional power of Indian kirtan music to millions around the world. Ecstatic fans have turned him into something of a rock star of Indian devotional music, making him arguably the most famous performer of kirtan in the history of a musical form dating back five hundred years. Certainly no one has done more to make this Hindu communal tradition more accessible to contemporary western ears, with over 300,000 albums sold. His music can infuse these soaring eastern melodies with a bluesy, rock ‘n’ roll spirit, where creative arrangements blend traditional and western instruments and rhythms. Whether in a church, concert hall or yoga workshop, engaging the audience is essential to creating the live experience of kirtan because the music is made by musicians and audience together, chanting the names of God in call and response.

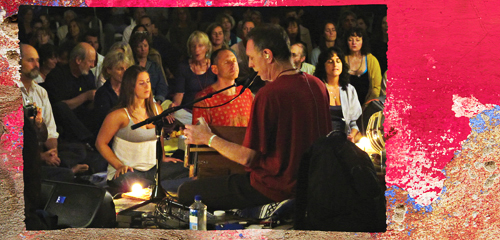

KD’s appearance as a kirtankar (one who sings kirtan) almost always draws a sell-out crowd. He had just finished a tour through Bucharest, Budapest, Prague, London, Moscow and Copenhagen before we caught up with him in New York, where he was prepar-

ing for an evening performance at the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew on New York’s Upper West Side last November. We spoke with KD during the sound check as the church’s sanctuary filled to standing room capacity.

Krishna Das’s story has been recounted by himself and others in many interviews and articles, but to summarize briefly: Jeffrey Kagel—his given name—didn’t grow up with the aim of becoming the world’s most popular devotional singer. Instead the “white Jewish kid from Long Island” was a blues freak whose heroes included blues legends Mississippi John Hurt and Bukka White. His early sights were set on a rock ‘n’ roll life. And it almost happened that way. At Stony Brook University Kagel joined up with an edgy amateur rock band but dropped out of the group before they morphed into the heavy metal group, Blue Oyster Cult.

Years later a chance connection with the American spiritual teacher Ram Dass set his life on a different course. Kagel became Ram Dass’s student and eventually followed him to India to meet his own beloved guru Neem Karoli Baba, called Maharaj-ji, who also became KD’s guru. KD recognized in Maharaj-ji a living manifestation of unconditional love. “My guru was completely unusual,” KD tells us. “He didn’t teach, he didn’t lecture, he didn’t write books. He hung around, so that’s what you did.” In India KD discovered the sublime joy of kirtan and threw himself into the music because Maharaj-ji enjoyed it—and it was a way to spend more time in his teacher’s presence.

When Maharij-ji died in 1973, KD’s life was thrown into turmoil and despair. The death of his beloved teacher was for him the death of love itself. What followed was a “freakin’ dark night of the soul,” as he once described it—depression, drug addiction and inner chaos. Love everyone, serve everyone had been one of his guru’s clearest teachings and KD eventually saw that singing kirtan with and for others would be his way of service. In his own words, “I wasn’t singing to become famous or become a star; I was singing to save my own ass.”

As the sound check continued upstairs, KD spoke with us about Neem Karoli Baba, what makes music sacred, and the personal meaning of an emotional journey to Auschwitz with Buddhist Roshi Bernie Glassman.

How do you describe kirtan for people who don’t know anything about it? For people who don’t know anything about it I could never describe it. Not in a few words. But for me chanting is a way I turn to again and again, to return to that presence that is always here, that we always forget.

And the practice of chanting is remembering. But I don’t tell people what they’re going to experience, or even what they should look for. Why should I? It just makes more work. Come, sing, here’s how you do it. If you have a good time you’ll come back. If not, see ya later. We can do something else. I’m not on a mission.

Is kirtan a bridge…? Yeah, but the only problem is the toll’s too high. You can’t afford the toll. You can’t even get onto the bridge! [laughter]

I don’t know what you know about my history. Twenty years had gone by since my Guru Maharaj-ji died. He died in ’73. And I hadn’t been chanting. I mean, I might’ve sung a little bit with friends and stuff but I wasn’t really chanting as a spiritual practice.

And I was standing in my room and I was struck with the understanding that if I did not chant with people, much to my chagrin, then I would never be able to clean out the dark corners of my own heart, myself. Chant was the only thing I had to do it with.

This was the only lifeline that was being thrown to me. There’s no question I was drowning. And I just knew that chanting was the only thing that would work for me. I mean I had been meditating, sitting with lamas, going to courses. I’d been doing things in my own way, but of course not allowing it to change my heart at all. That’s what we do. But then I knew chanting with people, that was the only thing I had.

Do you have an understanding now why that was the only thing? I don’t know why. It’s just what Maharaj-ji, my guru, gave me. I mean, we used to sing to him because he liked it, not because we were trying to be spiritual. He liked it and we got to spend time with him. We were, like, his performing monkeys, you know. When the Indians were giving him too much trouble, he’d call for the westerners to come in and sing.

What happens when you sing, when you use your voice? I can’t tell you because I’m not there…What happens is my guru picks up this old rusty pipe, blows through it, and makes nice music. And when he’s finished he puts it down. And people in the room, they experience the music he plays. It’s just transmission of his presence. And that’s what people feel.

People come to sing with me, not because I’m the greatest singer in the world and this is the best music in the world. It’s not. Personally, I would rather listen to Bruce Springsteen, or The Rolling Stones, or Steely Dan, or Ray Charles, or Van Morrison. But here I am and here they are. And what we receive is the transmission of my guru’s presence, which is the presence that lives within each person, that being that lives within us—the indweller. That’s who he is.

So he’s bringing everybody into that presence through me. And I suppose it’s good for me. He just knocks me out of the way and does his thing, but of course I invite him. At least he lets me think I invite him. [laughter]

But as I see it, he’s doing everything. And I want to surrender completely to him, which I can’t do because surrender comes from grace. So when he’s ready, he’ll surrender me. And my job is just to get ready, to keep chanting the name, keep listening, keep hearing.

He didn’t tell me to do this. I’m doing this to save my ass. And on the strength of that everybody else who comes is doing this to save their ass. It’s not entertainment for me and it’s not entertainment for them.

In the Vedic tradition, there’s what they call non-dual Bhakti. It’s seeing the non-dual in the dual, without any holding back. It’s seeing absolute reality right there in the dualism. It honors absolute reality and relative reality. They don’t think one’s better than the other. They honor both.

You see this in Rumi and Hafiz so much, just seeing the absolute divine in worldly love and the things that happen in daily life. And there’s just no separation, you know, no mental concepts to keep you locked up. I find that kind of devotion, that kind of love so liberating. Devotion is just love. You can’t work at love, you know. You can work at cleaning up your act, but love is what it IS.

You can work at the things that keep you locked out of your own heart, but what’s already in there is exactly what’s supposed to be there. And my guru was like that. We don’t know much about his tradition, but he used to talk a lot to us about Kabir and also about Samarth Guru Ramdas, who was a great saint I think in the 1600’s. He found the non-dual through devotion to Hanuman, devotion to a form. He went though the form into the non-dual. And he always said to people this is the way to do it. You can’t do it any other way. That’s what he used to say.

And what I get from that is that you can fully embrace this world and the forms that are in it. You have to fully embrace this world and bear witness to this world and everything that’s in it—all the beauty and horror. You can’t hold back and say, oh, I only believe in that which you can’t see, feel, think of, because how the hell do you know what that is? It’s just an idea in your head, and an idea could never be what it is. So it’s very difficult.

You said in an interview that your Guru is inside of you. Well, that interview must be over a week old. Completely changed my mind about that. [laughter]

Okay, so what’s the latest news? To talk about inside and outside is really oversimplification, to say the least. But since we have to use words and concepts it kind of gives us a nice idea of a concept that might be useful. There was a period after a few months, about nine months, I actually quit singing because I could see people attracted to me, and I could see I was hungry. When a person’s starving they’re going to take whatever bread, whatever food they find. Even if it’s rotten and ugly and full of mold they’ll eat it. And I saw I was going to use the situation to feed my hungry desires. And that horrified me because it’s not why I was doing it.

So I quit. And I went back to India, and I said to Maharaj-ji, I said, listen, if you don’t fix this I can’t sing. I don’t want to use this to get laid. I can’t use this to get power—look how powerful and popular I am going to be. You know why I’m doing this. I’m singing to you. So this is your problem, you have to fix it.

And I had no doubt that he could. I only doubted if he would. See, that’s a very interesting point in terms of relationship to the guru, or to the universe, or to God. I had no doubt that he could. No doubt…but would he? He might not. And I had such despair, I can’t even describe it because the only thing that I could do to save my ass I was being prevented from doing by my own impurities. And there was no way out of this box.

What happened next? He changed my heart. He pulled something out of me. And he brought me into a space which completely changed my life in terms of who I know myself to be. He showed me that “Krishna Das-ness” was nothing. And even when I thought I was Krishna Das I wasn’t. So it was okay to be stupid and think that I’m doing this. It would have no effect on what actually happened because the reality is that he’s doing it. And that freed me to come back and really sing, and not worry about anything.

And I saw that all these people who were coming towards me thought they were coming towards me. But they were coming towards that connection, that presence, the place, coming home, wanting to sit down and relax at home. That’s what they were drawn to. It looked like me to them but it doesn’t mean it has to look like me to me.

What makes music sacred? Music is not sacred. The intention with which music is done, that’s what makes it sacred. Music itself is just sound. If it was sacred all musicians would be enlightened, and they’re not. What’s sacred is what’s put into the music by the intention or presence of the being who’s doing it.

In this case Maharaj-ji’s putting his presence, his juice, his transmission into the chanting. That’s what makes it sacred. We’re chanting the names and these names have been revealed to us from beings who have entered into the presence through these names. They say that every repetition of one of these revealed names from any tradition is a seed, and sooner or later it’s going to grow according to the conditions. And one main condition is the intention of the person invoking the name.

Something is sacred if it is sacred. You don’t make it sacred. Sacred is what is. Everything else is what we think—who you think you are, what you think you’re doing, what you’re thinking about.

You can’t think yourself out of a box, out of a box that’s made of thought. Sacred is what’s all around that box. Sacred is the space, the presence that holds everything.

Would you call it remembrance? Remembrance is a good word. Remembering to look, remembering the name. But the thing is you don’t really—do you really remember God?

You just remember to look for it because you don’t know what you’re looking for, you don’t know what you’re remembering. Do we know God? We know the concept God, we know the name, the word God. But take Ram for example. For westerners, when you say Ram it’s like an echo that goes out into space and doesn’t come back, because there’s no reference point for the meaning in us. It doesn’t give you anything to think about. So your mind just quiets down and melts into the practice.

Those are just concepts. That’s what religions are. Religions are forts made out of bricks that people hide behind and shoot arrows and bombs at the other forts. It’s organized hatred, organized selfishness, organized violence. My god is better than your god. My god’s the only god and this is the only way. And I’m not going to let you live because you don’t believe this.

So that’s why I have nothing to do with religion. I’m not a Hindu, I’m not anything. I don’t want to be labeled because as soon as you label me somebody’s going to hate me. I want to be liked by everybody.

But that’s not possible. [laughter] Yeah. You think so? How do you know? [laughter] Well, maybe it is, I don’t know. I didn’t say it was possible. I just said that’s what I want. I want to be everybody’s friend.

Maharaj-ji didn’t make us Hindus. He didn’t initiate us and tell us to go forth and multiply. He fed us, he loved us and he sent us away. And then we had to find that love inside ourselves. And that has no label. You don’t need to join something to find what’s already inside of you. Do you need to become a doctor in order to know that you have blood in your veins?

There are other kinds of music that are part of this expression and connection you’re creating. You know the form of the music, which is maybe a little bluesy, rock-and-rolly, a little gospel, that’s how I grew up. I didn’t grow up in India listening to Indian music. And so what? You’re telling me God only likes certain music, only if you sing certain scales? How could that be? God likes when you when you let him come through.

Do you sing at home? Yeah, I do. Some. But if I sang at home I couldn’t give myself to it the same way that I can when there’s 1,000 people in the room. Just to be honest. I don’t care what anybody thinks about that. I told you what my revelation was, my epiphany. I had to do it with people. It was with people—how do you see those people, how do you sing with those people? I don’t give very much thought at all to how people are responding. Whether they like it or they’re getting off or not, that’s not my problem. You know, it’s not a concert.

Is it a different experience from place to place? No, it’s exactly the same everywhere. I mean some groups sing more, some groups jump up and down, take their clothes off, like in California. [laughter] In Switzerland, they sit very straight and they sing, but they don’t take their clothes off.

Everybody’s the same. They want the same thing, they want to be relieved and disburdened. And they want to be joyful. They want to find some kind of happiness, whatever they call it. And they’re all the same in their lack of ability to really do that.

The burden of just being. The burden of getting old, and hurting, and watching your friends die, and being sick, and seeing people blown up in the streets, and knowing the suffering that exists in this world.

It’s the same world, which we also have to love and embrace and hold on to. [long pause] I’m a little particular about words. I don’t use the words “have to” much if I can help it. And, I wouldn’t even use the word “love” there. I would say you have to really, as Bernie says, “be with it.” You have to bear witness to it, you have to develop a heart as wide as the world.

You know I was in Auschwitz recently. For five days we spent all day in the prison camp. And I was leaving and it was a beautiful day, a physically beautiful day, and the sun was setting over the gas chambers, over the ovens, over the ashes of a million-and-a-half people. And I said, “How can the sun rise over this miserable place? How can the sun rise over this place?” Because I’m sitting here, there’s nowhere to hide from what this is.

You have to let it in, you have to be with it. You’ve got to, you’ve got to, you’ve got to…talk to it, you’ve got to listen to it; you can’t pretend it isn’t what it is, because it is. And the sun rises over that horrific place every day of the year. How can the sun do that? Well, the sun is unconditional. The sun doesn’t judge. It shines on everything. On those miserable bastards who broke people’s heads with the butts of their guns just for fun, who ripped babies away from their own mothers and threw them directly into the ovens. The sun shines on that person as much as the sun shines on you and me. Now that’s hard. But that’s true.

So when we talk about love we have to deal with the space within us, the presence of our own anger, and fear, and shame, and guilt, and selfishness, and allow them to melt away so we can really be with this world. And the saints, the great beings know every bit of the pain in this world, so it’s all part of them, too. And you could say the Nazis are just as much a part of Maharaj-ji as anybody else. Since we’re all one. And that’s what love is.

So, I mean, this is who my guru is. He is that presence, he’s that oneness, that one. And when I sing, my job is just to sing. And anything I’m thinking about I let go of and I come back to the chanting. And gradually I settle deeper into this unmoving all-filling presence that is the guru.

I’m singing to him. I’m singing to that love and that love is in you, it’s in everybody in the room. And some day I’ll be able to really believe that it’s in those Nazis, because they’re a part of this, too.

Why did you go to Auschwitz? Because Bernie Glassman asked me to go. He’d been asking me for 12 years and I’ve been avoiding it. So finally I didn’t have a good excuse.

Your forefathers are Jewish, right? Yes, in fact they’re from Belarus. But my family left in the 1890’s. So by the time that happened it was already 50 years later. And I never heard about Auschwitz when I was growing up.

Wow. Never. Not a word in my family.

It’s called dissociation. It’s called not wanting to deal with it because they had too many people who died. They wanted to be happy. They wanted to go to Miami and sit on the beach. They swallowed all that suffering, and you know you can’t really blame them. It’s like a black hole, and we really fear that if we go into that black hole we’ll never come out. So I don’t blame my grandparents for not talking about it. What could they say? It probably destroyed them to some degree, the anger and the pain that they must’ve felt.

Why did Bernie want you to go? Because…because he goes every year. He’s been going there for 17 years. For 17 years they’ve been doing retreats there in Auschwitz.

Every year he goes, they spend a week there. And I would recommend it to anybody. At any time.

It’s very, very deep, very powerful. And I was scared shitless, to tell you the truth, before I went. I didn’t know whether I’d be able to deal with this, or whether I would close down and run away. I feel it’s part of the blessings of the place that along with the horror there’s something else there. I hesitate to use the word “love” but there’s something else there. There’s presence.

You’ve got to understand, we’re not trying to make love happen. When we bear witness to something it means you let it be what it is. And the love comes from within you, and you overcome your own anguish, anxiety and kneejerk reactions to things. I’m not saying I love those Nazis but…I’m willing to deal with the reality of what happened there, and not push it away, and try to really be with it.

My guru’s always saying you know, “All one. All one. All one.” All the time all one. So, this is what, this is what I go on. I take that as the truth that all paths lead to the same goal, that all beings are part of the same being. That’s the bottom line. And anything that doesn’t lead me towards that bottom line, I’m not interested. I want to be where he is. I want to be with him, and that’s where he is. And so I want to be in that love.

I followed a devotional path for 15 years where we did kirtan maybe three or four times a day and it seemed to open everybody’s hearts enormously while we did it. But it didn’t seem to translate into people being more loving or more kind. Can you say something about that? You know, we’re really good at doing a lot of practice, but we’re even better at making sure that that practice doesn’t soften our hearts at all. We just get big egos about doing practice and we don’t really allow it…You have to cultivate remembering kindness, and loving kindness, and caring, and compassion. If you just aim for blissful states of being you’re just going to be more greedy for those blissful states, and you’ll kick anybody who gets in your way. Maharaj-ji never encouraged us to do meditation or even to chant for the sake of our own spiritual advancement.

We said, “How do you find God?” He said, “Serve people.” How do you raise kundalini? Feed people. It’s not as simple as it sounds, but it’s also not as difficult as one might think. When we feed someone, we’re feeding the God within them. We’re feeding that oneness within them.

And the idea is not to be thinking about ourselves all the time, which is very difficult. And really the way most westerners do practice, formal practice, the chances of not thinking about yourself are very slim because the whole time you’re doing it, you’re, you’re intensifying the thought of, “I’m sitting here doing practice.” So how is that thought of me-me-me going to go away?

Do you think that’s because we westerners are so focused on self? It’s tricky for westerners because many of us are so locked out of our hearts. We’re so cut off from our natural sense of well-being. And the more we do, the further we get from that natural sense of well-being, which is already there. We’re theoretically trying to get in touch with that, but we’re doing more and more practices, and more and more mantras, and more and more this, and more and more that, and we’re forgetting who’s doing it, and why we’re doing it.

After my guru died I went around to a lot of saints and I asked them, you know, how can I find him? They would look at me like I was crazy and say, “Your guru? Your guru’s looking through your eyes right at this moment.” •

(Photo Courtesy of Krishna Das, Background © Bruce Amos Dreamstime)

Subscribe or Order the Current Issue Today!